When I read Walter Isaccsons biography on Leonardo da Vinci, aptly called ‘Leonardo Da Vinci,’ I was struck by two mysteries. The first—Da Vinci had some very, very, very questionable relationships with young men, and I’m going to try very hard to put that to one side.

Secondly, he did a lot more than paint the Mona Lisa. He pioneered in a staggering number of fields and was mostly self-taught. It took centuries for others to replicate his findings or validate his ideas. But that’s not the mystery. The mystery is, why old Leonardo never shared most of his history-making discoveries.

This is the animated video version of this blog piece on my Youtube channel. I’m working on putting more animated videos like this up.

Context

Let’s start at the beginning. Da Vinci was born in 1452 in Florence. A common theme with other subjects of Isaccson biographies is that they grow up as outsiders. Einstein, Steve Jobs and Elon Musk are examples of this. It could be that the outsider identity goes well with a willingness to reject conventional logic and explore new territory. Well, this was true for Da Vinci, who was homosexual, left-handed, vegetarian and the illegitimate son of a successful notary, so he was denied a formal education.

As Isaccson notes, ‘Florence flourished in the fifteenth century because it was comfortable with such people.’ This was the Renaissance, a time of rebirth in Europe, and Da Vinci is probably the emblematic Renaissance Man, a term used to describe someone with considerable knowledge or expertise in various fields. It wasn’t uncommon in Da Vinci’s time for people to dabble.

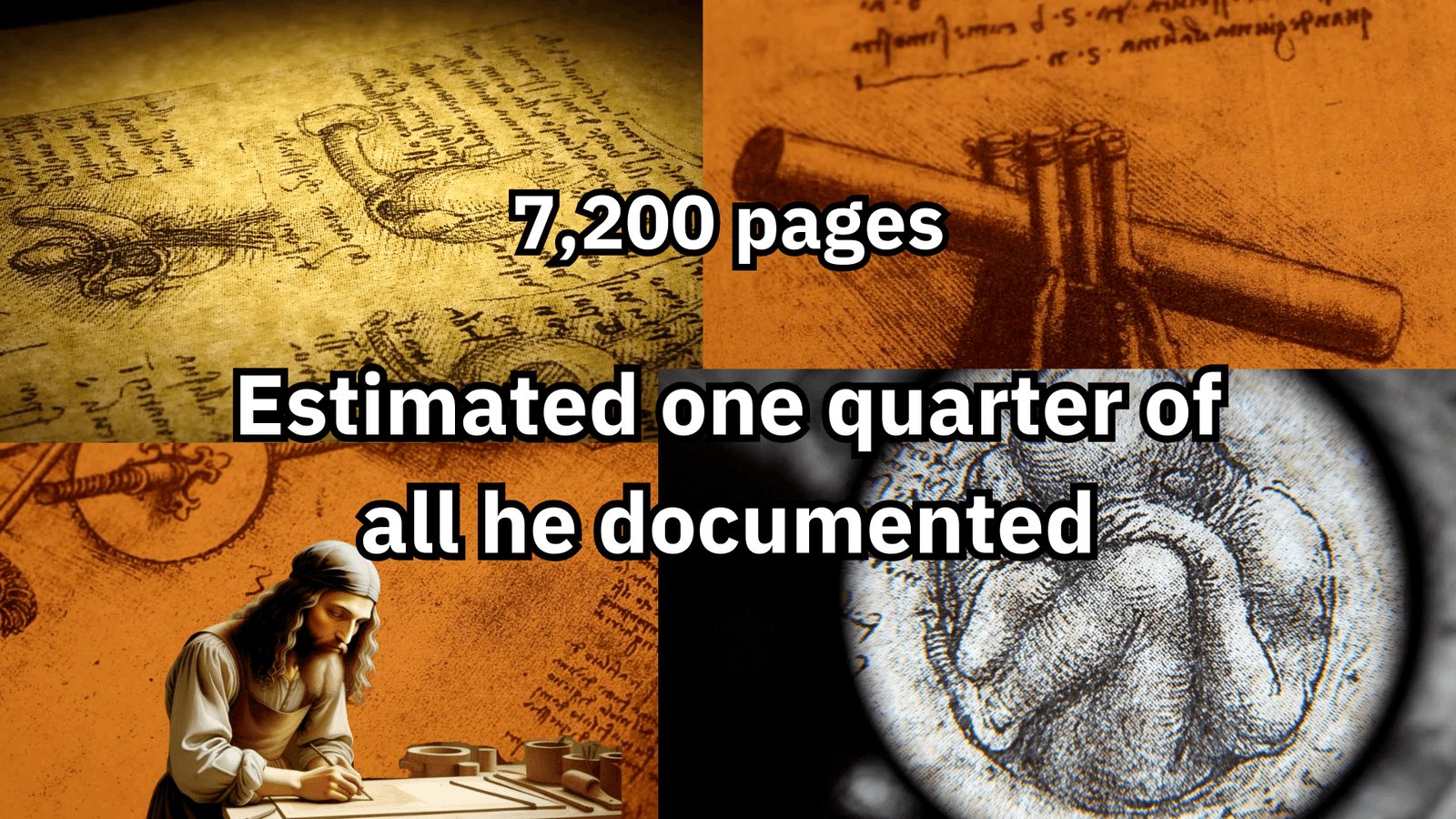

While Da Vinci never shared or published much of this dabbling, 7,200 pages of his private notes have been recovered since his death, which is estimated to be one-quarter of what he actually documented in his life.

These notes and sketches reveal his mind’s incredible wanderings and date back to around 1487—they include everything from sketches of different types of faces, and diagrams for cities and weapons, to strange lists of people to ask very specific questions, like ‘Get the master of arithmetic to show you how to square a triangle… ask Giannino the Bombardeir about how the tower of Ferrara is walled” Other notes were utterly obscure—Da Vinci set himself one reminder to ‘study the tongue of a woodpecker’.

Notes like these highlight one key thing about the famous polymath, maybe the very thing that set him apart and enabled his multi-discipline proficiency despite a lack of formal schooling.

Curiosity, or Obsessive Perfectionism?

Curiosity. Curiosity may have killed the cat but it looks like it drove Da Vinci, who never stopped at the surface of things. He looked at the same ball of string as everyone else but kept pulling. Let’s start with what he’s most known for—his painting and visual art.

In his notes, Da Vinci documented types of noses so he could recall them later, eleven types of facial shapes, he even measured a bunch of ratios in the body. He was obsessed, striving for a deep understanding of what he was painting, which drove his interest into related areas—light optics, physics, and his studies in anatomy, dissecting some thirty corpses during his life.

Master Experimenter

Da Vinci detested received wisdom and didn’t like to rely on books or other documented knowledge. He was incredibly self-directed in his learning, which in my experience, is common for people who stand out in their field.

He wasn’t always right, with many of his ideas being off track, and he failed often, but it never stopped him. He was the master of devising experiments to test his insightful ideas.

Most impressively, he used a bull heart as guide to make a glass model of the human heart. He filled it with wax, then sprinkled grass seeds in water so he could observe the flow. It took anatomists 450 years to realise Leonardo was right about blood circulation in the heart.

Master Procrastinator

He was also the king of rabbit holes, a slave to his interests and showed no regard for what we today would call discipline. By today’s standards, I’m guessing he would be diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). He would regularly abandon paintings and jobs he had been commissioned to do!

As his father and others knew when they drew up the strict contract for his commission, Leonardo at twenty-nine was more easily distracted by the future than he was focused on the present. He was a genius undisciplined by diligence. — Isaccson.

For example, he resisted the rich and powerful Isabella d’Este’s request for a portrait, but did one of a silk merchant’s wife named Lisa. He did it because he wanted to. He never bothered to deliver it!

Da Vinci’s notes, in their chaotic covering of every tiny facet of our universe speak to his insatiable curiosity, but I see another engine of achievement here, sitting in the shadow of curiosity: Obsessiveness, perfectionism, a desire of mastery Da Vinci injected into every domain he could.

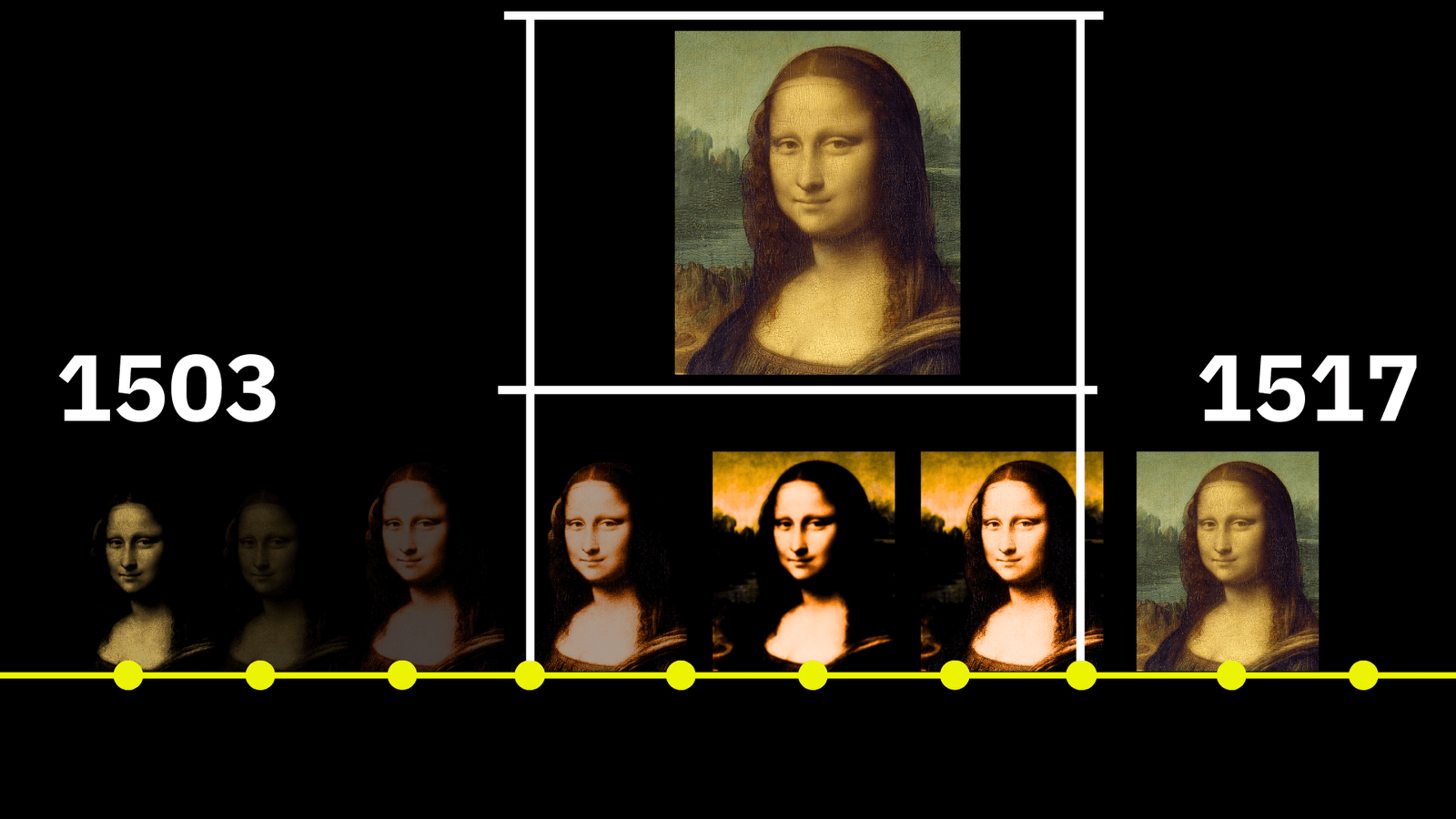

This is exemplified in his painted works, most notably the Mona Lisa—as the story goes, he worked on it for fourteen years, from 1503 to 1517, keeping it in his attic the whole time and continually touching it up. He had difficulty with anything being totally complete.

Whatever the driver, Da Vinci seems to have tapped into something deep about our world on his journey from observation and painting, to engineering and music, via anatomy and physics and dentistry and botany and everywhere inbetween.

Interconnectedness

Interconnectedness. Da Vinci saw the connection between all the things, when others treated them as discrete and separate entities. The best symbol of this is a painting technique he developed called sfumato. While other painters treated edges between objects with clear and defined lines, sfumato refers to Da Vinci’s technique of making hazy and smokey boundaries between objects.

To him, there was no clear start and stop between these parts of nature. Da Vinci started to paint differently because he saw connections others didn’t, and was big on metaphors and thinking by analogy.

In one of his musings about the ideal design of a city, Da Vinci reflected on a city being like an organism, as a thing that needs to breathe and has fluids that circulate, as well as waste that needs to move.

At the same time, he had started studying blood and fluid circulation in the body. It’s no wonder he kept going from one thing to the next—he kept following the rabbit holes, while noticing patterns that transcended individual fields and disciplines.

Some of Da Vinci’s most notable achievements are

- Being one of first to appreciate that the heart is centre of the body, not the liver

- Being the first to inject molding material into a human cavity, an act not replicated until two centuries later.

- His designs for an ideal city, though never adopted, “might have transformed the nature of cities, reduced the onslaught of plagues, and changed history” according to Isaccson.

He also performed music in live courts, wrote plays, made breakthroughs in physics centuries before Newton, stumbled upon innovations in dentistry and light optics, designed weapons like an engineer, and the list goes on.

Wealth

Despite it all, Leonardo was never a very rich man. He was social and very collaborative, exchanging notes and ideas while amassing a small following in his time, but rarely did he enjoy lasting financial stability. At this time period, the patronage system was alive and well in Europe, but Da Vinci always created for himself ahead of any patron or client. He had a very different idea of wealth and was clear on what he valued.

“Men who desire nothing but material riches and are absolutely devoid of the desire for wisdom, which is the sustenance and truly dependable wealth of the mind.” — Leonardo Da Vinci

Da Vinci wasn’t classicly religious but he was swept up in the awe of the world and universe, and interacted with it somewhat spiritually through art and science. His tale makes us question the tension between the organised world, with its commercial and economic realities, and the very different reality of people’s creative spirit, when fully and freely expressed, reminding us the two are not always harmonious.

It makes me wonder—do we edit and compress this spirit too much to fit inside the lines of our social structures? Is there value in giving more people the licence to freely explore?

As I mentioned before, Da Vinci wasn’t always right, but no matter the stumbling block he kept going.

Maybe that’s the benefit of prioritising exploration and discovery ahead of production, of looking to create things that are first of all pleasing to oneself before they might be pleasing to others. Did Da Vinci hold onto so many of his discoveries because he was too lazy to share them, or was he too distracted? Could he have been afraid? Was it selfish of him? We’ll never know, but one distinct possibility is that he was too lost in the universe to care.

My Biggest Lesson From Da Vinci

If I’ve learnt one thing from Da Vinci, it’s to cash in on being five hundred years ahead of your time. That’s why I’ve written books which are timeless classics. I thought of holding them back like old Leonardo, but in the end I realised they were just too good to keep to myself.

You could read Isaccson’s biography of Da Vinci, I mean, it’s a good read, but I just summarised it so well, freeing you up to give mine a go.

Jokes aside, feel free to check out the video or my other article on this last point, around the tension between the commercial, ‘practical’ world and the creative-authentic.

For more writings or announcements on book releases, sign up to ‘The Doorman’ below, or see more options at Everything Joe.